- Home

- Molly Crabapple

Drawing Blood Page 9

Drawing Blood Read online

Page 9

We thought we might pose together. We had complimentary looks—both pale as paste, but I had curves where she had angles. We talked till the café closed; then she invited me to her place in Harlem. On the subway, she whispered, “I don’t know how to flirt with girls.” It was the first thing she said that sounded soft.

We woke up next to each other on a mattress that took up the entire room.

Jen was dating a guitarist who worked in the stockroom at an organic food store, but he didn’t think that her sleeping with other girls counted as cheating. I looked down at Jen. She was so small in that bed, bird-frail, her skin translucent over her temples. I propped the door open when I left, found some orchids at a flower shop, and placed them next to her sleeping head.

Despite her Dartmouth degree and brief stint at a tech company full of Ivy League men, Jen was more working-class than me. She’d grown up in Virginia, the daughter of a housewife and an enlisted man in the navy, and she was the first person in her family to go to college. While she was at Dartmouth, the dot-com frenzy hit. White guys were getting millions in venture capital for ideas like Balls.com (Balls! Online!). Why couldn’t she? But she never knew the rich people’s trick of funding unprofitable companies with other people’s money. Instead, she tried to turn a profit by offering design services to paying customers. Within two years, she was bankrupt. She put all her worldly goods in a car and drove to New York City to try to make it again. Her car was burglarized the day she moved in.

Why did we sleep together, dubiously queer girls that we were? Desire is fluid, but I think Jen and I fucked each other because we wanted to stand by ourselves. Were we not sweet enough for men? Were they put off by our ambition, how fast we talked, how needy we grew? We wouldn’t contort ourselves for their desires. Our faces were the same size as we kissed. We were equals. We needed no masculine protection.

We would protect each other. We could protect ourselves.

The photographer Patrick Demarchelier had shot Cindy and Claudia, Naomi and Kate. His loft was one floor of a building in Chelsea, white, looming, adorned with blowups of his Vogue covers. When I stood in that loft, shivering in my kimono, the chasm between me and the women he’d shot loomed greater than it ever had on my midnights hunting for gigs on Craigslist.

Demarchelier’s assistant, Wendell, specialized in photographing vulvas.

That’s why I was there.

Wendell showed me his portfolio of vulva photography. Each was printed oversized in silver gelatin, and lit with the craft you’d expect from Patrick Demarchelier’s assistant. Every follicle shone like chrome. I nodded, feigning interest. Who cared how he’d shoot this anonymous bit of my anatomy? I was there for the four hundred dollars.

Wendell had designed a bed for his vulva photography—velvet-covered, rigged with stirrups, resembling a Victorian gynecologist’s table. His camera was equally archaic. As I read a fashion magazine, he expanded the camera’s bellows. Flash, then a puff of smoke.

I recommended Jen as a subject.

“When we are old and all our men die,” Jen told me, “we’ll buy a house and hang our vagina prints over the mantelpiece. If anyone guesses whose is whose, we’ll give them candy.”

I was not cool.

Cool is not needing. As I turned twenty, all I had was need.

I loved the profiles of careless rich girls that filled the pages of New York magazine. In their photos, they were all hip bones and rumpled hair and bitten, just-fucked lips. They wrote “Let god pay the bill,” and quit their jobs to smoke angel dust. They abandoned everything for months and were not forgotten.

Every story left a knife of envy in my ribs. What I would have given to be one of those girls. They were so glamorous, these blank girls on whom you could drape salvation. In each profile, the reporter swooned with love. “Fuck the world,” those girls could say, in their furs, their torn black stockings. Later I’d come by furs and stockings myself, but never that insouciance.

I didn’t know the rules of the worlds I was trying to conquer. I showed up at art openings and tried to shove my portfolio into the curators’ hands, always at the moment they least wanted to meet me. I got no shows. I printed up business cards on copy paper. Like everything I made, they stank of desperation. I gave them to old men who later emailed requests to spank me.

Every time I encountered someone I’d heard of, I’d think, “This is my one chance. I must make them love me.” They never did.

Maybe if I’d been from a different school or from a different class I would have grasped those rules. I would have known how to charm, whom to please. My path would have been less circuitous and hard. But my mom’s family—clueless, broke artists—never knew how anything worked.

The more I posed, the more tired I became. The more I hated all the pointless portfolio drops, all the long subway rides in the cold, all the mold colonizing the living room ceiling. I needed to make it. I had to try with every tendon in my body.

Posing did not come naturally. To look good on camera is an acquired skill. In my first pictures, I was flabby and young, achingly human. Hating them, I spent hours in front of the mirror, trying to find the exact muscular configuration that contorted my face into hot.

I learned to turn my head toward the light (it hides wrinkles), to suck my stomach in and arch my back till it creaked. I posed in icy rooms because cold air makes your skin firm. Each time I posed, I felt the vulnerability of my own flesh, its infinite flaws. When I looked at my photos, I saw a stranger staring back. I learned that photos are lies.

Eventually, I got better at posing, and better known. French fashion photographers took my picture. I preened in lavender lingerie on the pages of the car magazine Lowrider. When the photographer was right, shoots could be creative and collaborative—a chance to play dress-up, to pose and act for his or her camera flash. But they were a distraction too, from the images that only I could make.

My photographer friend Brian had a room on the second floor of the Chelsea Hotel. His wife, Melli, did makeup for Vogue, but Brian mostly shot Internet models. We’d writhe around in the checkerboard fantasia of the place while wearing pairs of heels from his own, improbable collection. The Chelsea Hotel was legend: the place where Sid stabbed Nancy, where Patti Smith lived and Burroughs shot heroin, where Janis Joplin once gave Leonard Cohen head on an unmade bed while limousines waited on the street. I loved the Chelsea Hotel, before New York killed it like it kills all its darlings.

One night, I lay on the couch with Vinyl Vivian and a friend of hers. Vivian’s hair was neon yarn, her pitted skin plastered with pancake makeup. She wore yellow lipstick. She told me that men paid her to worship her feet. Vivian was relaxing after a photo shoot with Brian, while I was preparing to start one.

Suddenly, an older lady barged in, gray curls flying, back straight with all the imperiousness of the well funded. She was someone important, Melli told me, doing a documentary on the hotel, but now she stood over us, ordering me and Vivian into passionless contortions. Startled though we were, Vivian and I writhed around gamely, like professionals. After ten minutes, the Belgian was gone.

Several years later, I saw myself on the cover of an art book, frozen in time with Vinyl Vivian. We were entwined, topless, and intimate as we never were in life. The text inside described an orgy that had never happened, starring nameless girls who we were not. The photographer described herself not as a director of the scene, but an invisible bit of the background.

She never told us we’d be on the cover. Why would she? We were hotel room fauna. National Geographic would sooner notify a giraffe.

America still believes that if you work hard enough, you’ll achieve your dreams. Go to college. Get a job. Put in the hours. The invisible hand will reward you with a home and enough money to take your kids to Disneyland. It’s a soothing lie. Any strawberry picker will tell you that hard work is a road to nowhere.

But for my friends and me, fighting our way to moderate financial success, money came f

rom transgressing society’s norms. It might have involved fucking rich dudes you met on Seeking Arrangements. It might have involved selling hallucinogen-laced chocolates, or shucking your clothes for GWCs.

It always required doing the ambitious work everyone said you weren’t ready for, then getting mocked and rejected for it, until, slowly, the wall of indifference began to crack.

Artists are not supposed to care about commerce. The lies told to artists mirror the lies told to women: Be good enough, be pretty enough, and that guy or gallery will sweep you off your feet, to the picket-fenced land of generous collectors and 2.5 kids. But make the first move, seize your destiny, and you’re a whore.

Naked-girl money was my escape hatch. Without it, I’d never have been able to do the work that got me noticed. I’d never have had the materials, the space, or the time.

When I was twenty-two, I spent some of my modeling money on mailing postcards of my artwork to a few hundred art directors. Between the cards, stamps, and list of art directors’ addresses, it cost me five hundred bucks—the entirety of my savings at the time. Days later, the New York Times’ art director called. She’d liked my postcard, and she assigned me a small illustration for the wedding section. It paid eight hundred dollars. It was my first illustration job for a major publication, and it led to more newspaper work. Most career breaks come this way. Talent is essential, but cash buys the opportunity for that talent to be discovered. To pretend otherwise is to spit in the face of every broke genius. I am good, but it was never just about just being good. It was about getting noticed.

I met Fred a few months short of my twentieth birthday. I’m still with him now. His body is hard and golden, etched with blue tattoos. He holds me when I’m crying real, ugly tears, grabbing me hard like I’m a little girl. He’s the only one who can talk to me the way he does. I cry and shake, and he’s there. He is kind and he is beautiful and he is mine.

In the mornings, he’ll poke me. “Get up, animal,” he’ll say, something he calls me because I’m feral. I expect to die in bed with him serving me coffee as he does each sleepy morning. I will be dead—and content.

I met Fred through Linda, his girlfriend at the time. Linda and I became friends after a random encounter on Bedford Avenue. Linda was an artist’s model, with long pre-Raphaelite hair and a fragile face, pointing at that vulnerability that fucks women over in the long run. That week, she was couch-surfing. Twenty minutes into our conversation she mentioned that she had no access to hot showers. I let her take one at my place. She showed me the work of her boyfriend, Fred: brilliantly painted caricatures for Time and Sports Illustrated, the colors juicy and the lines depraved. I wanted to know how to draw like that.

She spoke to Fred, and he hired me as a model for the drawing groups he held every Thursday.

Fred and his wife had an open marriage. Her boyfriend sometimes lived with them at their loft on Pearl Street in Dumbo, its gray walls piled with decades of paintings, orchids climbing the windows. One Tuesday night, I posed for six artists while they drank wine. I wished I were drawing alongside them instead of holding painfully still on the model stand.

As I posed for Fred, I stared at him. He wore combat pants and an undershirt, worn thin and stained with paint. Fred had long blond hair that made girls confuse him with a romance novel cover model. His wide shoulders narrowed into the V of his hips. I liked men who were too tall to sit normally, so big they held themselves awkwardly in chairs, their legs splayed apart. I liked bruiser men who moved through the world with a paradoxical gentleness. Fred had long fingers, covered in calluses. He held his brush with great care. I couldn’t help wondering how his fingers felt.

His studio was filled with art. Paintings of Johnny Cash and the pope stood on easels, the color stroked lovingly into every wrinkle and wart. Stacks of flat files, piled high with papers. Ink drawings stuck to the walls. By his desk, a low glass palette with a rainbow of paints, bleeding into each other like someone had murdered My Little Pony. Giant nudes, eight feet across, painted with brushes as big as heads. The women in those nudes were ugly and beautiful all at once, seemingly slashed open with each paint stroke, their lips full, their legs spread. Fred painted men with cocks larger than these girls’ arms. The work had a machismo to it, and a violence. I wondered how it felt to be so unconstrained with paint, swinging my arm, slashing it, confident that each brushstroke would land right.

When it was time for a break, I stole a look at Fred’s sketchpad. I regretted it immediately. He’d given me a hooked nose, sagging tits, and a swollen, pendulous gut. The other guys worshipped him, so they followed suit, competing over who could make me the most hideous. I mocked their drawings, while secretly wondering how accurate they were.

Fred grew up in Rust Belt Pennsylvania, shooting pool and working in his family’s bar. His dad gave him his first gun when he was ten. He brought it to school for show and tell. This raised no eyebrows. Everyone had hunting rifles where he grew up, and the first day of buck season was practically a holiday. Fred worked his way through college doing caricatures at the carnival and as a muralist, adorning malls across the Midwest, with rococo clouds and vast hallucinogenic sunsets. The fumes made him sick every night, but he slogged till dawn drawing a comics portfolio anyway, until one day Marvel hired him to draw Conan the Barbarian. He’d been an illustrator ever since.

After I finished posing, I took out my sketchbook. I was still fighting between the rendered Victoriana I did for myself and the washes, vine charcoal, and oil pastels I was learning in school. The pages were unsure attempts, but I was proud of them, if only because I kept plowing forward. Fred leafed through the sketchbook, spending time on each page, and giving me thoughtful comments.

“You can draw so well. Why did you make me look so ugly?” I asked, grinning at him.

He looked back incredulously, then broke out laughing. He told me that he liked big noses, so much that, during high school his French teacher had banned him from her classroom after spying his rendition of her nose as a giant hook. He swore he meant no harm.

Smirking, I grabbed a pencil off his desk and started to draw him. I exaggerated his brow ridge into simian grotesquerie, then gave him squinty cross-eyes under it. I made his upturned nose into a pig snout, with nostrils big enough to fit fists inside.

“How do you like it?” I asked.

He liked it very much.

Fred was a member of the Society of Illustrators. Founded in 1901 in the mold of an old-fashioned private club, the society was housed in a two-story townhouse on the Upper East Side. Its cherry lacquer door opened onto a collection of Rockwells and Leyendeckers. Within a week of our first meeting, Fred got me a gig modeling for their life-drawing nights. While I posed, a jazz band, fronted by a tough blond singer, played the defiant anthems I loved.

When I posed at the society, I wore black stockings, pretending I was Bijou in Delta of Venus. Being scantily clad implied a persona. Being naked meant being meat. But my devotion to costume didn’t extend to work: I fidgeted during poses, or read books.

Behind the oak bar, an Irish bartender named Mike poured drinks. Mike kept alive the last hints of a decadence that had lingered since the society’s birth, since the days of Winsor McCay and Norman Rockwell. By 2003, its past was visible only in the black-and-white photos hanging in its bathrooms.

After I finished posing, I sat at the bar with Fred and the older illustrators. I asked them about school. Most hadn’t graduated. I asked what brushes they used, what paper, what ink. The illustrators were obsessed with art, but they saw it practically, like the working-class craftsmen they were. Fred bought me my favorite drink, the sticky, mint-flavored grasshopper. He then walked with me through the upstairs rooms, pointing out the color contrasts Leyendecker used to make his beautiful boys pop against the backgrounds. These were booze-fueled nights, overwhelmingly male. Most nights ended at three A.M., with Mike pouring us all free shots, and me passed out against Fred’s shoulder.

The

first time I slept with Fred, it was with his girlfriend Linda. I was dating a rich boy who repeatedly told me that he was entitled to a threesome, and that I ought to provide a female friend for the purpose. But Fred was so sweet that I told Linda we ought to sleep with him instead. We brought up the idea with dorky smiles, and soon we were having the impersonal sex that threesomes always devolve into—job-interview sex, cleansed of feeling, so no one would get hurt. People got hurt anyway. By the next morning, Linda was in tears, convinced that Fred liked me better because I was younger. A few weeks later, she screamed as much at him on the sidewalk outside CBGB after an art show where I had some work. He stared back, incredulous. He’d thought I was just another girl, who would be out of his life within a month.

Linda broke it off with Fred. I kept coming to the loft on Pearl Street, climbing the cement stairs and slipping behind him as he worked.

With each visit we grew closer. One reason was that we were both artists who were deeply committed to our work. Fred’s wife nourished artistic ambitions she had done little to fulfill, and Fred’s illustrations provided the vast majority of their income. Fred and his wife both came from the same rural part of Pennsylvania, and married young. After twelve years together, they had grown apart, and he retreated to his studio to avoid fighting with her.

Over bleary breakfasts, Fred taught me how to make art—not as a student, but as a professional. His were not the cookie-cutter lessons I still suffered through at FIT, but the hard discipline of seeing. He ordered me to draw hands across dozens of sketchbook pages, till my own hands ached. This repetition engraves itself as muscle memory—making art closer to ballet than writing.

But Fred also brought out what was individual about my work. He showed me mechanical pencils and ultrafine Japanese nibs that would work with my finicky style. He told me I didn’t have to paint big, or force myself into the mold of what art school taught me I should be. If I liked the obsessive, kitschy detail of the Venetian painter Carlo Crivelli more than Tintoretto’s cloudscapes, I should follow my compulsions. I began to find that my art came from my flaws as well as my virtues—that art was as intrinsic and unfakeable as handwriting.

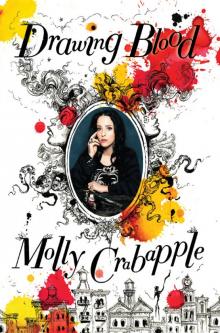

Drawing Blood

Drawing Blood