- Home

- Molly Crabapple

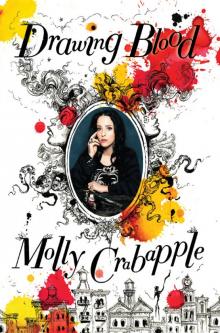

Drawing Blood Page 10

Drawing Blood Read online

Page 10

In exchange, I modeled for Fred. It was hard posing in the house he shared with his wife. I felt small and stripped bare as I lay frozen on the model stand, telling myself he’d never be mine. He painted me sprawled across his white sheets like an odalisque. Afterward, I put on one of the kimonos he kept for models and looked through his ink bottles. He drew a naked girl next to each of them, to demonstrate the ink’s transparency. I dipped a nib into the bottle, touched it to the thick cream Arches paper, and started drawing my demons across the page.

Slowly, I told him about my ambitions. But he didn’t belittle me, as I’d feared. Instead, he promised to help. He guided me through the process of doing sketches for art directors, framing my work for gallery shows, polishing myself up to function in the adult world of commerce and craft. He believed I could make it. With his encouragement, I began to believe it too.

I told myself at first that this was a temporary thing. I liked having a lover who was also a mentor, but I was twenty and I had a world of living to do. Besides, he was married, and what man leaves his wife for a naked model seventeen years his junior? I slept with Jen some nights, and a fashion photographer, and a beautiful Puerto Rican army vet whose muscled biceps were ringed with tattoos. I didn’t realize that I loved Fred until one morning when I left him to head home. I sat in the High Street subway station, choking back tears so hard that I doubled over. He was so kind to me, but it was a gentle, goofy kindness that he extended to everyone. I wanted it for myself. I needed him so much, it shamed me. I felt stupid for letting myself feel anything at all.

I refused to let myself tell him I loved him—directly, at least. Instead, I started writing him notes in Arabic. “I love you I love you I love you,” I scrawled, concealing my sentiments in calligraphic loops. I stared hard at him, hoping he’d somehow know what I meant, but he just smiled and told me how to better plan out my portraits.

One night, six months after we first slept together, on that bare mattress on the floor of my tiny room in Williamsburg, Fred brushed the hair out of my eyes and told me that he loved me more than anyone in the world.

A half hour later, I got up and walked to the bathroom. I splashed my face with cold water. In the mirror, I saw everything I hated in my face—my round cheeks, the bags under my eyes—but for a second it all flipped for me. I could see something else there now: a witch’s glamour. He’d told me he loved me. I had wanted it so much.

“I won,” I whispered to myself. For that moment, I believed it.

But Fred was still married, and every night he went back to his wife. I worked, I drew, I modeled, and I wondered how much longer I could go on being second best.

One night, I was working a go-go platform, wearing a lace bra and PVC hot pants. My fellow dancer had teased my hair before the gig, but it had long since collapsed. Glitter had melted into my cleavage. One fake eyelash hung off with Clockwork Orange precariousness. I danced as hard as I could under those strobes, and swallowed a caffeine pill when I got tired. The crowd danced around me without noticing me. Gasping, I wondered how many more hours I had left in the shift.

Then Fred walked in. With his wife. Jealousy gutted me. She looked so legitimate—this attractive woman in her midthirties, in a black tank top, confident, laughing, clean. She wasn’t like me—shaking with fake desire, exhausted, her makeup leaking down her face. She was The Wife. I was a disposable slut.

I kept dancing, pretending not to notice. I felt Fred’s wife glancing my way, but we’d reached an unspoken détente. Fred said hello to me briefly, then left.

My shift finally ended, long after midnight. Afterward, I stood alone in my room, my body singing with pain. I slowly took off the fake hair, platforms, bustier, and lashes. With each item I removed, more pain and tiredness leaked out.

The tangle of girl accouterments on the floor was almost as big as I was.

Broke white kids though we were, it took a year for us to fulfill our role in the gentrification process. By summer, the landlord kicked my roommates and me out of our Havemayer Street apartment.

I found a sixth-floor walkup two blocks away on Roebling Street, a dingy flat with black walls and no refrigerator, that the landlord described as needing a “woman’s touch.” There was no sink in the bathroom, and instead of a shower, a hose extended from the wall above the claw-foot tub.

Over the last year, I had gotten close to Richard, a Puerto Rican metalhead who worked at a bike shop nearby. On his off hours, Richard welded bikes into Frankenstein-style war machines. He sold these double-decker monsters to hobbyists who jousted on them beneath the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. When the store was slow, we sat on the sidewalk, talking about our families, about hipsters and Puerto Ricans and white kids colonizing the neighborhood, and where we stood among them. I asked if he wanted to be my roommate.

Fred helped me move in. He was spending more and more time with me, and fighting more and more with his wife.

I installed checkerboard linoleum, hung up a baroque mirror inherited from my grandmother, and stapled up dollar-store plastic flowers to hide the cracks in our crumbling walls. Richard installed a shower. John and I hauled furniture off the street and painted it gold. Over a desk abandoned by a former tenant, I hung a portrait of Napoleon I’d bought at a thrift store when I was thirteen.

One drunken night I forgot my keys. The super showed me he could pick my lock with a credit card. The same super looked through my trash. He found naked Polaroids of me smeared in jam—detritus from some modeling shoot. “I’m saving them,” he said with a grin. “Now I know what you look like with no shirt.”

The landlord hung flyers in the hallway that read “Stop urinating in the stairwell. We know who you are.” Each was adorned with an inverted photograph of an eyeball. The flyers were part of the landlord’s attempt to upscale the building. One night, the super painted the forest green hallways white, the better to see every building code violation. “Like SoHo,” he told me proudly.

I was part of the building’s gentrification, too. My pale face would lure yuppies like another coat of whitewash.

Our first year together, Fred refused to take me to the Society of Illustrators’ awards show. He wanted to bring his wife instead. Going to the awards show was their tradition, and he wanted to demonstrate that their marriage still worked.

I resolved to go anyway. I may have been his girl on the side, but I was also an artist, and I refused to hide in my room. That year, the society was presenting an award to the illustrator Michael Deas, for a painting I’d posed for. He invited me as his date. I blew my savings on a white Marilyn Monroe dress. I wanted to be as conspicuous as possible. But when we walked into the room, I saw Fred alone by the bar, drinking his third whiskey. His wife and he had been fighting. She never showed up.

At the next awards dinner, six months later, Fred invited me instead.

The society was honoring the cartoonist Jack Davis, from Mad magazine, and Brad Holland, a famous illustrator from the 1980s. Both men received rings representing their lifetime achievements. Over drinks, Brad took out his new ring to show his friends. It slipped from his fingers. I saw it bounce across the carpet.

Instantly, I dove for it. I stood up, slipped the ring on my own finger, and grinned like a monkey. The society’s photographer snapped a picture.

Brad was the only one in the room who smiled for real.

I sat in the bathroom of Barnes & Noble, squinting in disbelief at my second pregnancy test. I’d been throwing up for two weeks, unable to hold anything down but mint ice cream, and yet when I saw those indisputable two lines again, I had to force myself to acknowledge they were true. My mother, though prochoice, had always conveyed to me that abortion was for stupid girls, teens who didn’t know how babies were made, not clever girls like me. This passivity is baked into the grammar: “impregnated,” “knocked up.” Yet no matter how free or clever I believed myself, there I was. Knocked up.

I leaned against the wall of the stall and let the pain hit

me like a punch. Then I hyperventilated till I calmed down, and started planning what I’d do.

For me, whether to have an abortion was never a question. The only question was how soon. I have never had maternal instincts. Babies were alien to me, so fragile that when an aunt passed me hers I thought its neck would break. And there were other considerations: Fred was still married. I was eking out six hundred dollars a week by virtue of a relatively pert body.

But it was more than economics. Unwanted pregnancy feels like womanhood at its most hateful and cowlike: the broodmare inside the bombshell. You are yourself, full of wit and dreams and adventure, until you discover that biology has been conspiring against you, to sicken and trap you. Nature cares nothing for individuals. The embryo in me felt like an invader; it represented the end of any future I might have dreamed.

In that moment, I understood why women pre–Roe v. Wade stabbed knitting needles into their cervixes. Abstract debate meant nothing while I was throwing up every hour, just wanting to be the way I’d been before.

Before it happened, I’d resolved that I wouldn’t tell Fred if I got pregnant, that I would tough it out by myself. But I was so ill that I knew I’d need someone just to take me to the clinic. I called him up. He paused for a second. I could hear him running through the script: not wanting a child, but knowing that a good man tells a woman he supports her choices. I could sense how scared he was that, despite everything he knew about me, I might decide I wanted a baby.

I told him not to worry. I’d get rid of it.

School got harder. Frustrated by a dean who wouldn’t transfer his credits, John quit. He was my only friend at FIT. I sat alone with forty aspiring artists in an advanced illustration class, gessoing brown craft paper, then soaking it in turpentine. The turpentine made the brown transparent, and the white even brighter. The fumes left me so dizzy I had to support myself against a chair. I waited for the turpentine to dry, then, carefully, as our teacher had taught us, crosshatched a self-portrait, half on the white gesso, half on the oily brown craft paper. The materials wouldn’t obey me. The ink bled on the brown. The nib caught on the white. It looked like everyone else’s self-portrait.

This was so futile. Our professor no longer illustrated professionally, yet here we were, her forty clones, mimicking a style that had failed her.

I came to class later and later. What was the point?

Pregnancy felt like a mixture of stomach flu, clinical depression, and a damp gray blanket wrapped around my brain. Every day on the freezing subway platform on the way to school, reeling with fever, I’d think about throwing myself on the tracks.

The day before my abortion, I posed naked for a series of pinup skateboard decks. Before the shoot, I sat with the other models in the cavernous studio eating stick after stick of gum. By then, it was the only thing that wouldn’t make me vomit. Stylists shellacked my hair, painted my mouth, and propped my body into the painful contortions favored by classic pinup artists like Gil Elvgren. It was a demanding shoot, but I was glad for the candy-hard artifice of it. I would be tough and cheerful. Smile fixed. Shoulders back. Willpower over biology. I would brazen it out against my own body.

The next morning, Fred and I headed to a Planned Parenthood clinic in Manhattan. Outside the building, two old men were standing on the sidewalk, one faded cut-up fetus placard between them. It was hard to tell which was more tattered, the men or their sign. A girl entering before me flipped them off with relish. I grinned, then flipped them off too.

Planned Parenthood was the city’s cheapest, best-known clinic, and it was run like a combination assembly line and prison. Hundreds of women filed in past metal detectors, mostly broke, mostly brown.

Fred came with me, paid for the procedure in advance, then left. Because Planned Parenthood is a terrorist target, no one is allowed to accompany you past the clinic’s front room. You sit surrounded by other women. You wait for your abortion alone.

It took seven hours to complete the full round of blood tests and ultrasounds. In between, I waited. The long delays and bureaucratic tangles just made me angrier—not at the clinic itself, but at a country that could put such facilities under constant siege. I was determined to be cheery and cordial. The receptionists may have barked at us while we gave them our four hundred bucks, but they were risking their lives.

Finally I spoke to a counselor. She was an older black lady with dreadlocks and a gentle, practiced smile. “Is anyone forcing you to do this?” she asked, reading from her checklist. “No,” I mumbled, forcing back tears. She was the first person in the clinic who had been kind to me.

In the changing closet, I took off my clothes. I looked down at myself, seeing my red knees, pale nipples, every blemish and hair. A standard-issue, knocked-up female body.

There are only two ways out of this, I told myself. Some pain now. Or all the pain later. I put on the paper gown.

“I’m not taking my sneakers off,” said a woman outside my little changing cabin.

“Then you’ll get your baby on your sneakers,” a nurse responded.

Holding my possessions in a plastic bag, I walked to the operating room. I got onto the table and put my legs in stirrups. The doctor was the first man I’d seen in the building. He asked me about my job. It seemed so trivial, this bit of humanizing banter. I now know that it’s a technique doctors use to distract their patients from pain. “Artist,” I tried to answer, but the nurse kept stabbing the back of my hands with the IV. He missed the vein, hit bone. I jerked away. He yelled at me to stay still. That was the last thing I remembered before the twilight anesthesia kicked in. Later I replayed that moment with hallucinatory vividness: hating myself for how I’d yelped. I’d wanted so badly to be strong.

Then it was over. I was on a gurney, one of many, each with its own female cargo. Then I was stumbling off with a bloody pad between my legs, holding myself up against the wall, wobbling as I changed back into the clothes that reminded me who I was. In the recovery room, a receptionist gave me a painkiller.

I sat down next to a young Dominican woman. She was beautiful, her pale eyes catlike on her smooth, dark face, her cheekbones high and her hair slicked back. We smiled at each other sheepishly. “How are you?” she asked.

“Fine,” I said hopefully. “And you?”

She told me she had two children, whom she loved like hell. The fathers of both had pressured her to go through with the pregnancies, but both men were in jail now, and she was working two jobs. When she got pregnant the third time, that man had also wanted her to keep it. “I’m never trusting one of them again,” she told me, laughing. “They say they’ll be around, but they’re not.”

“Men,” I laughed back. Men, even the sweetest men, poison us. For the next generation to exist, we get sick and swollen and our ribs stretch outward; finally, our bodies are torn apart to get the baby out. Some of us die in the process. The man? He has his orgasm, then walks away.

That feeling, as we sat chewing our graham crackers and exchanging pleasantries over pain, was one I’d recognize again when I was sitting with fellow protesters in a Manhattan holding cell. It was solidarity.

The process lasted a full workday. After I was steady enough to walk, Fred picked me up, ushered me into a taxi, fed me lentil soup, and put me to bed. John dropped by, looking miraculous in a white suit, bearing flowers and anecdotes about the fictional abortion in Cabaret. My roommate Richard poked his head in my room to tell me I’d done the right thing. I tried to make conversation, but I could barely lift my head. Then the men all left: Fred to his wife, John to his boyfriend, and Richard to his job at the bike shop. I was alone.

I lay in the dark, trying to fall asleep. But my mind started spiraling. I was so stupid. So fucking stupid. Stupid trash, splayed on an operating table, the nurse thinking I was pathetic for moving my hand. At least it was out of me. But I had failed, because it was in me in the first place. I was stupid trash. I had failed. I remembered a photo I’d seen of a woman who had needed

an illegal abortion in the days before Roe v. Wade. Without a doctor, she and her boyfriend had tried to do it themselves. They had some surgical tools, a textbook, and a hotel room. The wire he threaded up her cervix punctured something. Once she started hemorrhaging, the boyfriend fled. She was found dead by the hotel maid, lying on a berber rug, thighs caked in blood made black by the film stock. Her face was hidden. She was as vulnerable as a dissected frog.

The woman loomed in my head, crucified because she’d wanted pleasure or love and to live on afterward. I put on some Ella Fitzgerald. I wanted brave music. I saw that woman, saw myself in that woman, gigantic behind my eyelids, and the music sounded hollow. I screamed into the pillow, tears pouring from beneath raw eyelids.

A week after having a surgical abortion, all patients are supposed to get a follow-up exam. I never did. Haunted by memories of the nurse yelling at me as he tried to insert his needle, I couldn’t make myself go back.

I should have gone. The hallucinations I had the first night turned into a fever that left me barely able to stand. I took a week off from modeling and school. It was winter. When I forced myself to walk through those ice-slick streets, I’d have to rest on a lamppost just to keep going. “Be tough, you stupid bitch,” I’d tell myself. I stopped handing in assignments.

“School is a reflection of the real world,” my editorial illustration teacher lectured me one day after class. “If you can’t succeed here, you won’t succeed there.”

“I was . . . sick,” I told him, but from the frown on his face I knew he didn’t believe me, and I didn’t want to tell him what sick meant. Without John there to mock him after class, I groused alone, pacing fluorescent-lit halls hung with clumsy oil paintings cranked out by the previous semester of failures.

Drawing Blood

Drawing Blood