- Home

- Molly Crabapple

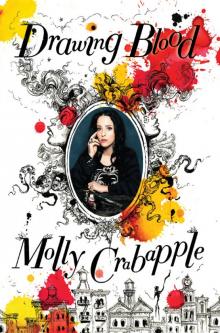

Drawing Blood Page 6

Drawing Blood Read online

Page 6

We spent a month in Morocco, lying next to each other in cheap hotels in whitewashed mountain towns, where the doors were so blue they dreamed the ocean. I wouldn’t sleep with Russell. No matter how far Anthony and I had drifted away from each other, I clung to the notion that, as long as I wasn’t having sex with Russell, I wasn’t cheating on my boyfriend.

Before we fell asleep, I read to Russell from a book of his about twelfth-century Europe, including the story of Abelard the theologian, who had a mad love affair with his brilliant student Heloise edging on blasphemy—they even fucked on the altar—until Abelard got Heloise knocked up. Then it all went south: Heloise’s uncle cut off Abelard’s testicles; Abelard joined a monastery; then he badgered Heloise until she joined a nunnery, where despite her disbelief, and her anguish at his abandonment, she ascended to the role of abbess. Russell listened and sulked, frustrated, meditating angrily in the mornings. “Either we make love or I stare at a wall,” he said. I declined, without much apology, then left him so I could go sit in the streets and draw.

The tour groups clomped through Fez’s medina, lugging huge cameras worth two months of an average Moroccan’s salary. I watched one tourist jam her camera into the face of an elderly bookbinder, who’d been quietly working in his alcove. Flash, flash. Other tourists did the same with the metalworkers, local kids, harried moms shopping for groceries. I hated them. In my mind, drawing was distinct from photography. After all, I told myself, you take photos, but you make art.

One afternoon, I curled up on filthy steps with my sketchpad. Before long, a half-dozen street kids had gathered to watch. None of them was older than eight, but they had hard, smart little faces. They ran in gangs, sniffing glue and bumming cigarettes, using their cuteness to cadge a few dinars from tourists. Drawing was my monkey dance to prove that, despite my dopey American face, I still had skills I could rock. I drew the kids, writing their names in careful, misspelled Arabic, then tore the pages out for gifts. They scampered away with my sketches.

I looked up, and my eyes met the disapproving stare of a vegetable vendor who wore the long beard and shaved mustache of the religiously devout. With a scowl, he walked over, tore the page out of my sketchbook, then shredded it with a self-satisfied grunt.

As he left, I started to cry. Like any self-centered tourist, I thought he stood for all Morocco—that the whole country had rejected me. Back at the hotel, I told Russell what had happened. “It’s because you’re an infidel,” he told me, before launching into the story of his day.

Our hotel had no showers, so we went to the hamam, or public bathhouse. After paying an entrance fee, you received a bucket and some soap from an attendant. You filled your bucket out of a communal pool, then washed yourself out of the bucket.

Russell told me he’d tried washing off his travel stink directly into the pool. The other bathers, seeing him dirtying up the water source, shouted at him to stop.

“They didn’t want to be made impure by an infidel,” he declared thoughtfully. I rolled my eyes at him.

The next day, I returned to the vegetable seller’s square. A teen boy stopped me. “Sorry about the guy who bothered you yesterday,” he said in English. “He’s crazy.”

He shoved something into my hand. It was my drawing, taped back together like a broken arm.

Russell liked to fight. He’d liked to fight as a young street kid, and as he grew older he channeled it into martial arts. He felt most at home when he found a martial arts gym in Fez’s new city. He introduced himself to an instructor, and within five minutes they were on the mat, gleefully pummeling each other, then laughing and slapping each other’s back. On the way home from the gym, we walked through a dark underpass. Russell held my hand. We heard footsteps behind us. A voice shouted, “Cover up your woman.”

Russell turned, shifting his weight like he wanted to attack. They were three teenagers, handsome and lanky in their tracksuits.

“It’s just how things are,” I whispered to Russell, tugging his arm to get him to move on. Of course, that was how things were in New York too—this is how things are everywhere—but I didn’t bother mentioning that.

Back in the hotel, he told me it was my fault.

It was always my fault—every time I got hissed at or groped, every time an old man eye-fucked me after leaving a bus station. At a café, we had tea with two Swedish backpackers. They were good girls, blond and windburned, wholesome as cheese. “They don’t have these problems,” Russell told me.

I was not good. My eyes were too intense. My hips wiggled when I walked. I wore a floor-length skirt and one of Russell’s shirts, but the skirt still outlined my ass like a shelf, and when I moved the shirt gaped at my tits.

“Even Marilyn Monroe could turn it on and off,” Russell said. “You can’t.” If I kept traveling alone, he warned, I was sure to get myself raped.

We took buses deeper into the south. The land turned treeless, an endless expanse of baked clay. The Modern Standard Arabic I’d studied bore nearly no resemblance to the type spoken in North Africa, but once an hour I’d pick up phrases. When I did, it had the thrill of magic.

Merzouga was a village on the edge of the Sahara dunes, filled with local guys hawking tours of the desert. They wrapped indigo scarves over their faces in imitation of the Tuareg nomads tourists expected to see.

“Don’t wear shorts,” I told Russell. “Shorts are for little boys here, and no one wants to see your knees.” I pointed out how neatly most young Moroccan guys dressed, in button-down shirts and pressed trousers. Many of the older men wore loose djellabahs.

His first day there, Russell wore shorts anyway. A little girl threw a rock at his head.

Russell later wrote about the incident. In his article, the small rock turned into a near boulder, and the girl herself into an avatar of primordial evil, lusting to bash in his skull.

None of it was true. She was just a girl with her friends, seeing a gringo in shorts. He must have seemed teleported in from the other world, where grown men dressed like children.

He was weird. Kids everywhere gang up on weirdos.

She threw the rock. Her friends laughed. It meant nothing.

Russell hired a guide and we walked into the desert. I hadn’t wanted to. I was broke, and I hated the idea of being guided. “Lawrence of Inania,” I scolded him. But when we walked into the Sahara, we entered the landscape of dreams. This was the world Dalí had painted. I took off my shoes. My feet sank into powdery sand. The dunes stretched out before us, a blanket rolling into the infinite.

On our first night in the desert, I lay next to Russell, staring at the sky. The stars shone like holes punched into the dark. They were so far away. We would die and they would never know. The universe was vast, amoral. What was loyalty beneath that sky?

I turned to Russell, who was staring at me. I reached for him, sliding my hands beneath his shirt.

We stepped off the bus into Marrakesh. A muscular young man in a tight T-shirt passed us, followed by a couple on a motorbike, the girl’s thighs, lacquered in skinny jeans, hugging her man. “Town air makes free,” Russell mused, recalling an old maxim from medieval Germany: if a serf escaped to a city, and remained there for a year and a day, he would be liberated from his master. Marrakesh did feel free. It was an electric, cosmopolitan city, with all the urban anonymity that implied. We stank like hippies, our clothes were torn and sun-bleached, but no one gave us a second glance.

The Square of the Dead is at the center of Marrakesh’s old city. The storytellers and dancers in the square took the tourists’ Orientalist fantasies and repurposed them into a machine for the extraction of foreign cash. Scowling young guys donned fezzes and held monkeys. If a tourist wandered too close, the monkey jumped on him, clinging until his victim paid a ransom. Dentists tended to teeth as entertainment. Berber acrobats piled high atop each other’s shoulders, hoping to be noticed by talent scouts for circuses. Women painted palms with henna, squeezing miraculous curlicues from pastry t

ubes. The henna looked like Cheetos dust on white girls, but on brown ones it resembled dried rose petals.

Russell and I were no longer fighting. After our night together in the desert, he had a momentary affection for me, and as I saw him walking down the old city’s streets, I recognized the swagger I’d once adored in France. I admired his ease, his grifter’s smile, his violence in reserve.

Each morning, Russell wrote in a café, taking breaks to smoke hash with local guys. His was the public world, which is to say the male world, of bars, drugs, and easy camaraderie. I envied him.

On his last night in Marrakesh, Russell told me he wanted a future together. I could leave Anthony, move to the Northwest, we could travel. I didn’t even consider it. After a month together, I couldn’t help feeling that despite our twenty-year age difference, I’d outgrown him.

Once I’d thought that a man who was older than me must be all-knowing—braver, smarter, better. My head might have been a masochistic tangle, but if I could please a man like that, I’d thought, maybe I’d be redeemed.

But that older man wasn’t Anthony. Nor was it Russell. That was a role no human could fill.

I kissed him ravenously and pinned him to the bed. Afterward, we walked to the train station. I looked at his blue eyes and broken nose, his shoulders strong in that faded T-shirt. Then I watched his car pull away.

As Russell disappeared, I grew giddy. I checked out of our hotel and found another one, free of memories. The walls were sky tile, the bedspread brocade; an orange tree grew in the courtyard. I sat on the rooftop, drawing the smoke that rose off the Square of the Dead. I was alone. I knew no one in the entire country. I was free.

Babies are cute so you don’t kill them. Young artists must be arrogant so they don’t kill themselves.

When I wasn’t at FIT, I devoted myself to gaining a foothold in the world of working artists. After class, I sat in the bookshop and copied down art directors’ addresses from magazine mastheads, then sent them crumpled sample art, my cover letters marred with fingerprints, pleading with them to give me a chance. Whenever I opened a reply from an art director, I braced myself for the inevitable “Thank you for your submission, but . . .” I permitted myself twenty seconds to feel the pain.

My mother advised me to become an art teacher, so that after thirty unhappy years I could get a pension. I ignored this, as I did most of her advice. Nonetheless, she taught me three important things:

1. Don’t illustrate other people’s books for free.

2. Don’t move to the suburbs, because commuting sucks your blood.

3. Don’t get into debt.

Instead, I sought out trendier artists. One hot painter agreed to meet me for coffee. He sat across the table, his eyes crimson from a long bender, and told me he’d never done anything to pursue success—it just happened. I later learned that “just happened” was code for being rich, well connected, or surpassingly brilliant. I was none of the above.

After many phone calls, I nabbed an interview with Steve Heller, the art director of the New York Times Book Review. As I sat in the sleek Times reception area, my head swam. This was it. I was about to be discovered. But Heller just flipped casually through my portfolio without really looking at my work. He paused briefly on a drawing of a porn star I’d done for the New York Press.

“We tend to focus on commissioning intelligent art,” he said.

Since I was fourteen, I’d consoled myself by walking the maze of the New York Public Library, and that’s where I went then. I walked the stacks, letting my eyes glaze over, until one book’s red spine snapped them back to the present: Explosive Acts: Toulouse-Lautrec, Oscar Wilde, Félix Fénéon, and the Art and Anarchy of the Fin de Siècle. It proposed an intoxicating history: Oscar Wilde was not just a dandy but a socialist revolutionary. Toulouse-Lautrec was a lacerating class critic. Anarchists drank with poets before setting up bombs.

I gobbled up one chapter after another, the afternoon’s disappointment fading in the light of 1890s Paris. When a guard came to warn me that the library was closing, I borrowed the book. I kept renewing it for months, until its theses had stained my brain. Though I was the daughter of an artist and a Marxist, I’d always feared that politics had to be grim and art had to be frivolous. The book showed me another way. Art and action could infuse each other. A painting didn’t have to hang in a gallery, dead as a pinned butterfly. It could exist in spaces where people cared, as a mural, a stage set, a protest placard. Art could be gorgeous, engaged and political, working defiant magic on the world.

Politics weighed on me that winter. The war in Afghanistan continued, and each week the White House announced a new enemy: Iran, Syria, North Korea, Iraq. Bush may have been a boy king dolled up as a cowboy, but the bombs were real, and by February he’d chosen where they would land.

With an attack on Iraq looming on the horizon, antiwar groups called protests. News of these barely touched my school; unlike most other New York universities, FIT was largely apolitical. Instead, I found out about them from graffiti scrawled on subway billboards, or stickers slapped around lampposts near Astor Place.

I was the only student in my class who walked out when the antiwar groups called student strikes—and the only protesters I knew were the crew from May Day Books—but I marched every day I could, in New York and in DC. The first time I saw the White House was over the shoulders of the black bloc, as they masked up, linked arms, and prepared to tear down a fence. Some five hundred yards away, a gaggle of paunchy pink counterprotestors howled in spittle-flecked rage.

If I was going to oppose the war, one man screamed, I ought to be raped by Saddam himself in a dungeon built for the purpose.

I held hands with the boy next to me because we’d forgotten to bring gloves.

For the last year, politicians had been calling for blood in New York’s name. Telling them to stop was our—my—obligation. Though the Iraq War endangered few of us, the protests filled all kinds of personal needs. Among other things, they were thrilling. Bonds formed running from cops are sweet with adrenaline and rage.

For the length of a march, we might have convinced ourselves that we could have an effect on geopolitics—and to the rest of the world, we proved all Americans weren’t howling for war. Thanks to the media portrayal, our protesters had less effect on our countrymen. Middle America saw us as freaks. We sneered right back at them, blaming them for Bush’s election. Outside the big cities, the carnival aesthetic of the marches played poorly. At one march, I saw a group of girls in fishnets and strap-ons calling themselves the Missile Dick Chicks, posing while fondling their weaponized cocks. Beside them stood Reverend Billy, a performance artist playing an anticonsumerist televangelist in his dirty white suit. The puppets posed, too, because there are always puppets. After five hours, I returned to my East Village apartment, hands blue and heart pounding, to scratch out an assignment for FIT.

On February 15, antiwar groups coordinated protests in six hundred cities. More than four hundred thousand people marched in New York. Police tried to pen us in, but there were too many of us. We unhinged the barricades and leapt into the streets, then ran, outflanking the cops, our legs pumping up Fifth Avenue until we reached the New York Public Library. Thousands more protesters had taken over the steps. We cheered them, roaring from our chests.

We took over Broadway until it was an ecstatic mash, our bodies moving to ubiquitous protest drums, drunk with protest’s lovely and treacherous delusion: There are so many people—this has to work.

“Fewer people showed up to that march than attended the first weekend of Kangaroo Jack,” Leavitt smirked. I was standing next to him at an afternoon vigil in Union Square, awkwardly holding a drawing I’d done of Bush as an imperial slug. John’s hands were empty. At that point he was still presenting himself as a kind of aristocratic conservative; he’d joined me because our anatomy teacher let us use the vigil as an excuse to skip class.

“I don’t think that’s true,” I snapped back.

“They’re just a mob, with no idea why they’re here. They’re dirty hippies and I don’t like them.”

“Why don’t you join the army if you like the war so much?” I asked.

“I can serve my country better as an illustrator.”

He started to walk away, out of the square and toward the art deco gates of a nearby bar. I ran after him. Neither of us had fake IDs, but the bartender didn’t ask.

When I wasn’t protesting, sitting in class, or drinking with John, I earned a little cash drawing smudgy pictures of people’s kids. In the school’s computer lab I haunted Craigslist, a classified ad website that exemplified the digital utopianism of the early 2000s. In that garden of text, you could sell a goldfish, a blowjob, an ottoman, your love. It was a place of entrepreneurship and freedom, as well as deep sketchiness, as shown by one early job I found there, doing storyboards for an indie horror flick. Thrilled to have a gig, I worked on the drawings while sitting next to John in the FIT cafeteria. Unlike me, he was on the meal plan. He ordered hills of French fries for both of us, so I didn’t have to pay for food.

When it came time to pay me for the storyboards, the director presented me with a homemade coupon in lieu of cash. It showed his hands photoshopped over a woman’s back, and offered one free massage, courtesy of him.

In March, Bush declared war on Iraq. I heard the news from the May Day crew, who sat eating foraged pastries in the courtyard of Saint Mark’s Church. On the cobblestones, they spread out cannoli and croissants in a pauper’s banquet. Despite the promises of the White House, we had never believed the war would come. Now we blamed ourselves. We’d screamed and marched and waved our signs, but the bombs were all queued up to drop on another country, and we were still here, unable to stop the death.

Drawing Blood

Drawing Blood