- Home

- Molly Crabapple

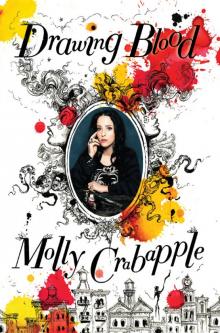

Drawing Blood Page 4

Drawing Blood Read online

Page 4

When we heard that the first plane hit on the café’s radio, I thought it was an accident. A bomber once smashed into the Empire State Building, I knew, on a foggy day in 1945. But on September 11, there was not a single cloud.

Then the second plane hit.

I rose, walked out the door, then strode fast down Eighth Avenue. A single thought repeated inside me: I have to see the towers. As I ran south, white eclipsed the familiar buildings of Soho, along with the crowds, streaming north. I didn’t stop till the smoke burned sour in my nose, and I saw a man, dust coating his office clothes, shuffling with fatigue in the opposite direction. “How are the towers?” I asked.

He turned to me, his face incredulous. “They’re gone.” He stopped, sobbing.

I turned around, and walked back to the dorms. Inside, the students crowded around their TV sets. Again and again, the jetliners hit the towers, penetrating the glass walls. From each hole, fire exploded bright as funeral carnations. Papers fluttered from the offices. Then the towers began to fall.

I called Anthony in Howard Beach, an hour and a half away by subway. The phones were jammed. I dialed till my fingers ached. He picked up.

“I knew you’d be okay. Somehow I knew,” he said.

I listened to the other students crying. I couldn’t cry. There was a coldness inside of me, like from a puncture wound. The shock before the pain sets in.

I curled between my blankets and drew the towers streaming smoke.

In those days after 9/11, flyers bloomed on every wall in New York, posted by family members searching for husbands, sisters, and children. But the faces on those flyers lay buried beneath the rubble of the World Trade Center.

After a few months, the families who posted those flyers stopped hoping. But the flyers stayed up for years, fading until the sun and mold made them illegible; they became the city’s scar tissue.

Then winter came and the country changed forever.

Ds New Yorkers breathed in the dust of their neighbors, the rest of the country threw itself into voluptuous hysteria. Politicians and the media both painted America as the ultimate innocent. The Muslim world hated us inexplicably—for our freedom, not for our bombs. How could this happen to us, the media cried. Death happened elsewhere; we inflicted death elsewhere, but this was America. We were supposed to remain untouched.

The city may have become a symbol, but we were still New Yorkers, practical and mercenary. Cafés collected blood donations. Street vendors sold vials of crushed charcoal briquette to tourists, claiming it was Ground Zero ash. American flags sprung up on halal chicken carts, frail defenses against the racist attacks to come.

Classes began at FIT, a grim complex of buildings from the 1970s so sparsely funded that the students didn’t even have enough easels, with required classes in the archaic skills—airbrush, marker rendering, doing type by hand—that my mother had mastered, before computers made them irrelevant.

Most Fridays, I took the train out to Howard Beach to see Anthony. At Penn Station, national guardsmen stood by with AK-47s, grasping the leashes of bomb-sniffing dogs. I climbed the steps to the A train. A homeless woman sang “Ave Maria,” her clothes and shopping cart stippled with neon paint. She must have been a professional opera singer, I thought, and I showed her my sketch of her, grinning. I tucked a dollar into her cup.

An hour later, I was sliding beneath the blue comforter where Anthony was sleeping off his night shift. We fit well, in the room away from our lives. I still listened to him when he told me his dreams, and I lied to myself that they might come true. I didn’t want to disturb our world. The room had no windows, so I could never tell what time it was. I tasted the sweetness of his sweat.

Winter came. On break from school, I bought a ticket back to Shakespeare and Company.

When I got there, the store was nearly empty. I had my own room, with a moss-green bed and a circular mirror, louche with age. The shower was broken, so we Tumbleweeds used public ones. My wet hair froze into icicles on the walk home.

One morning, on the way to get coffee at Panis, a little French boy stopped me.

“American?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“America. Coca-Cola. Osama.” He gave me a thumbs-up.

I worked the cash register on the last night of 2002. The European Union had just implemented the euro, and everyone was turning in old currencies for us to change. Irish punts, Italian lira, French francs. I pocketed a Greek drachma with the head of Alexander the Great, thinking it would give me luck. Afterward, an Egyptian boy took me to the Arc de Triomphe for the New Year’s celebrations. We danced together, dodging the fireworks revelers shot directly into the crowd. The euro symbol shone in lights on the bridges, as a trademark for the new era.

We nursed our hangovers at a party on January 1.

As usual, I did not participate. It would be years until I learned how to speak at a party, to do more than whisper passionately with Anthony or Nadya, or with others as odd as myself. I sat in the corner, words choked down in my throat.

Instead, I read Omar Khayyam. It was the edition illustrated by Edmund Dulac, which I had first seen when I was fifteen at a Long Island library. Heart racing, I had cut out all the illustrations with a razor blade, then smuggled them out of the library, hidden inside my Spanish textbook. I was ashamed by the defacement—hurting a book was blasphemy—but the illustrations shone so exquisitely, I couldn’t stop myself. Looking wasn’t enough. I needed to possess them.

An American guy sat next to me and looked into my book. He was in his forties, blond, beaten around by life. His face was scratchy with graying stubble, and his pupils burned tiny in his sleety eyes. But we looked at each other with that outsider’s understanding, and suddenly, I could speak.

His name was Russell, and he’d come to Shakespeare and Company the night before. I brought him over to Panis. We sat at the green zinc bar, drinking pale pastis that burned our mouths, and I read him lines from the Rubaiyat: “He who harvested the golden grain . . . and who threw it to the wind like rain.”

I brushed the gold hair from his eyes.

Holding hands, we crossed the river to the Île de la Cité, and walked into Notre-Dame. Alone, with the church vast around us, we lit candles in the silent dark. We sat next to each other on the pews. I lay my head on his shoulder.

Russell had grown up mostly in group homes around San Francisco, but since then he’d traveled everywhere. He told me about dropping acid as a sixteen-year-old runaway, and how the hallucinations were the one thing that could beat the pain in his head. He told me about buying the first Sex Pistols record when it came out, about beating a guy bloody on the streets of the Mission, growing up, getting sober, getting his masters, and ensconcing himself in the satisfying solitude of the Northwest mountains.

Hypnotized by his stories, I didn’t notice that the church had closed.

“Think you can last till morning?” I dared Russell.

He nodded. I blinked. I found a priest, gave him helpless eyes. He led me out.

The next morning, Russell showed up at Shakespeare and Company, looking as sweetly wrecked as his old leather jacket. He’d spent the night at Notre-Dame, then hopped the fence in the morning.

I brushed his pale hair aside and kissed him hard. He’d broken a rule because I’d asked him. Kissing him just seemed like the right thing to do.

The next day, we walked side by side in the Paris catacombs. Long ago, monks had arranged the bones into patterns: spirals, crosses, hearts. Christians believed in bodily resurrection. I imagined the jumbled bones flying out of the crypt, ordering themselves midair, clothing themselves in muscle, then in skin, to ascend whole into heaven.

We walked through the frozen streets to the Oum Kalsoum Café. Over hookahs and sticky sahleb, we decided to catch a bus to the south of France. On a cold Parisian night, whimsy can pass for magic.

We found a town too small to have ATMs. The sole hotel had decorated its reception room with butterflies in

glass boxes. Above one, the proprietor had written, “I am sorry. I used to do this, but no longer. You’re more beautiful when you are living.”

Russell always carried a copy of The Tempest. When we weren’t arguing, I lay in bed reading it to him. “The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces, the solemn temples, the great globe itself, yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve. And like this insubstantial pageant faded, leave not a rack behind.”

He wrote those lines on a notecard. Long after we parted, I hung it on the walls of every home I had.

Back in New York, school seemed even dimmer. During one art history class, the professor earnestly informed us that Titian sent a commission back to his client with a leg unfinished in order to express the fast pace of change during the Renaissance.

“No, he blew a deadline!” I wanted to scream.

Afterward, I wandered through FIT’s library. In the art history section, I let my fingers trail over the spines of the books, hoping the greatness would rub off. My finger stopped on a history of Islamic architecture.

It was an old book, bound in cloth. When I picked it up, it fell open in my hands. The page it turned to showed a ruined castle nestled in the foothills of Mount Ararat. The castle was made of pale stone, a mass of domes and peaked arches, with a striped minaret that looked like one of Dr. Seuss’s hallucinations. “Ishak Pasha Saray,” the caption read. It was the most beautiful building I had ever seen. The castle was perched on the Turkish-Armenian-Iranian border, on the far end of a region still wracked by civil war between the Turkish government and the Kurdistan Worker’s Party, a seperatist guerrilla movement more commonly known by its initials, PKK.

I felt a sharp tug in my chest. This building was so lovely, and so far away.

I promised myself to draw it from life.

That summer, I boarded a plane to Turkey.

Anthony told me I was stupid for wanting to spend three months in the country. I could tour all of Europe in that time. I didn’t tell him about my plan to see the castle.

I spent a month in Istanbul. Most mornings, I walked in wonder down the city’s main commercial artery, Istiklal Caddesi. It seemed like the grandest boulevard in the world, lit by fairy lights. I walked past the chestnut sellers, the döner kebab shops, the men hawking tar-thick ice cream from Kahramanmaraş, past the street cats and bubble blowers, the crush of couples hand in hand. I walked down the hills to the Bosporus, where gulls swooped over the riverboats, each topped with domes that recalled the mosques of Sultanahmet. The words of Turkish are short, the grammar so logical that Esperanto cribbed its structure, and I began to develop a shaky faculty with the language.

at Talking Points Memo (talkingpointsmemo.com)

After a few weeks, I boarded a bus and headed east toward the Iranian border. It took from five to eight hours to get between cities. The farther we got from the coast, the poorer the country became. Once we passed Kahramanmaraş, military checkpoints grew frequent. At each, the bus would stop and soldiers would stride through, checking our passports.

Just as Montana differs from Manhattan, eastern Turkey differed from Istanbul, being far more conservative. Men and women weren’t allowed to sit next to each other if they didn’t know each other. On the ride between Gaziantep and Mardin, I had a formidable older lady as my neighbor. She took a half-melted chocolate from a pocket in her modest raincoat and shoved it under my face. I ate it, oblivious that I might have brought some treats to give her in return. I stared through the window and sketched, tracing rolling green hills and silver roads connecting nowhere to nowhere. Turkey’s pledge of allegiance lay written in block letters on the side of a mountain: Ne Mutlu Türküm Diyene. “How happy are those who can say they are Turks.”

The conservatism played out in other ways. In Şanliurfa, a city near the Syrian border, I smiled too long at a hotel clerk. He pounced on me, trying to force his tongue into my mouth. I shoved him off. He looked embarrassed to have misread the situation.

The next day, I set off to explore the city. The old parts of Şanliurfa had an almost primal beauty: shades of gold and honey, domed and leafy, the buildings fading out into the hills. But there were no tourists here, and as an American teenager, I was painfully conspicuous. I sat down by the Balikli Pool, surrounded by walkways and old stone archways, and started drawing. Next to the pool was a shrine to the prophet Abraham. Old men sold fish food in the adjacent park. Religious visitors crowded by the water, feeding thousands of greedy carp.

As I walked out of the shrine, a group of police officers sidled up to me. They were handsome young men, tall and swaggering, with guns swinging at their sides. “Come with us,” they tried, in English no better than my Turkish. They walked close beside me, walling me off. I followed.

At eighteen, I still trusted the cops, and I didn’t realize I was being detained until we walked through the door of a tiny police station, past their laughing colleagues and dozing police dogs. They were probably jandarma, or military police, boys my age slogging out their mandatory military service. It would have been dull work, I can see now, stuck far away from the cities, checking passports in a region where, because of the war, most locals hated them.

At the time, I saw only their guns.

I was not handcuffed, but neither did I hope I was free to walk away.

Finally, one of the officers demanded, “What are you doing here?”

“Drawing,” I offered, in Turkish.

“Show me your passport.”

He stared at the battered pages. “I thought you’d be Russian,” he smirked, referring to the Eastern European women who did sex work in the region. Then another officer offered me a glass of tea.

The cops seemed identical now: just men, and frightening because of that. I thought I’d be raped. Then one cop laughed. “Why are you wearing that long skirt?” he asked. “I see what American women dress like on TV.”

I started to cry. The cops looked at each other. Suddenly they seemed young again, embarrassed as the clerk who’d tried to kiss me.

“Come with me,” said the first cop. They piled with me into a van and deposited me back at the hotel. When he saw me, the clerk laughed heartily at my expense.

The next day, I called Anthony. I told him about being detained, how I had sat with those cops at the card table, drinking tea, unable to leave, and how nice they’d been when I cried. I couldn’t figure if I had been in danger, or if I had brought it on myself. I tried to laugh the encounter off, but I was nauseated with my vulnerability.

When I finished, Anthony stammered a few awkward phrases before saying good-bye. As I sat, listening to the unfamiliar Turkish dial tone, a guilty pride filled me. Till then, I’d always seen Anthony as far smarter than I was. For the first time, I realized, I’d seen something he’d never experienced.

The city of Hasankeyf had stood for eleven thousand years, built atop caves where kids still played. Cinder-block homes clung to the rock face, and Roman columns poked out of the Tigris River. In the summer of 2002, however, the Hasankeyf was slated to disappear under the waters of the Ilisu Dam. The government had offered business owners compensation, but at a small fish restaurant along the river, the owner told me it wasn’t nearly enough for him to relocate. The restaurant’s plastic tables were set down right in the river; our feet dangled in the water as we talked, and I sketched imperial ruins in the distance.

Overhearing our conversation, a short, muscular man strode over to us. He had a neat beard, and dark curls fell over his forehead. With a slight Bulgarian accent, he introduced himself as Victor. He was a photojournalist working with a crew on a documentary about water politics around the Tigris and the Euphrates, and as he spoke he pulled out a small portfolio and showed me his pictures. A Burmese monk standing stiff before a gold pagoda. Laborers in Chittagong, Bangladesh, breaking apart decommissioned ships for scrap metal. He’d shot the ships from a low angle, so they towered above the thin, diesel-smeared men. I turned the pages greedily, demanding more stories.

With a gentle smirk, he lit up a cigarette and continued.

War journalists are some of the last macho archetypes we can lust after without ambivalence. They chronicle violence without being violent themselves. Victor hadn’t covered wars, but he had traveled to dangerous places, and in that Hasankeyf afternoon, I adored him and was jealous of him all at once. A photojournalist could see the world, meet all the people, and witness everything I clumsily tried to capture in my sketchbook.

Victor’s crew was headed to Doğubayazıt. I hitched a ride. I’d been in Turkey for three months, and I wanted to see the castle I came for.

Victor found a small guesthouse. It was little more than a cinder-block cube, with the ubiquitous Ataturk portrait sandwiched between action-movie posters in the front room. The owner didn’t have many tourists come his way, so he was glad to sit around with his friends and talk to Victor about the war. Many of his friends had lost family; some hinted that they’d been in the PKK. They were hard men, their faces clawed by the sun, and Victor loved shooting them.

But we’d been there only a day when Victor’s editor called to say the assignment had been pulled. He and his crew left. I remained. It didn’t feel like a choice. I had come this far to see that castle. I also had a low-grade fever, and I wanted to stay in one place. As I lay on the mattress on the floor of my room, growing sicker, a sensuous passivity overcame me. I was alone, escaped from my context. What would be, would be. I lay in bed, reading Crime and Punishment. Raskolnikov’s fever grew worse, and so did mine.

The next day, I hauled myself outside, sat down on a plastic chair, and stared at Ishak Pasha Saray.

It looked nothing like the photos. Sometime in the last few decades the government had renovated the castle, and someone’s relatives must have gotten the construction contract, because they’d done a hack job. Contractors had topped the whole thing with a metal roof befitting a suburban Walmart.

Drawing Blood

Drawing Blood